Zelf was ik er niet bij toen folkmuziek hip was in de jaren vijftig en zestig, maar ik luister graag naar oude Bob Dylan-songs. Dankzij de Coen Brothers krijgen we een aardige impressie van hoe die tijd was voor sommige folkmuzikanten, in de persoon van Llewyn Davis. Dat Davis een fictief personage is, doet daar niets aan af. Hij staat voor alle muzikanten die niet wisten door te breken bij een groot publiek en zijn leven is nogal mistroostig.

Davis was vroeger een duo met zanger Mike en samen maakten ze muziek die in het verlengde ligt van wat duo’s als The Everly Brothers en later Simon & Garfunkel maakten: harmonieuze, lekker in het gehoorliggende folk-songs. Nu Mike er niet meer is, moet Davis het alleen rooien. Hij sleept zichzelf van optreden naar optreden en van huiskamer naar huiskamer, waar hij bij vrienden op de bank slaapt. Zelf heeft hij geen huis, daarvoor verdient hij te weinig geld met zijn optredens.

Dit beeld herken ik uit Chronicles vol.1, de autobiografie van Dylan die beschrijft hoe hij in huizen van vrienden verbleef toen hij zijn eerste stappen in de folk-scene van Greenwich Village zette. Ik kan me pagina’s beschrijving herinneren, vooral van de huizen en de vele boeken die hij in de woningen van zijn vrienden vond.

Tijdmachine

Inside Llewyn Davis is geen vrolijke film. En Davis is in beginsel ook geen sympathieke hoofdrolspeler – al zet Oscar Isaac hem fantastisch neer. Zoals ik al schreef: ik was er niet bij, maar dankzij film kun je in een tijdmachine stappen en tijdperken zien waar je zelf nooit deel van hebt uitgemaakt.

De decors in Inside Llewyn Davis zien er getrouw aan 1961 uit. Het moet veel moeite gekost hebben om al die oude klassieke auto’s te vinden waar de straten vol mee staan. Om nog maar te zwijgen van de passende kleding, koffiekopjes en het behang uit die tijd. De sfeer in de koffiehuizen voelt authentiek – voor zover ik dat kan beoordelen natuurlijk. Het beeld lijkt aan te sluiten bij wat ik van die periode weet; ik ben geen expert, slechts een liefhebber. Ook is alles gefilmd in soft focus wat het beeld zachter maakt, alsof we door een nostalgisch venster terug in het verleden kijken.

Op de site die ter promotie van de film in het leven is geroepen, staan interessante artikelen over de productie waaronder de moeite die production-designer Jess Gonhor had om alles voor elkaar te krijgen:

Production designer Jess Gonchor says, “It’s getting harder and harder to shoot a period movie in Manhattan. It’s changed so much.” For Gonchor, the toughest job was reimagining the wall textures and room space of his Gaslight Cafe in a Crown Heights warehouse. He also transformed an East Harlem church into a seamen’s union office—and, given a tight budget, shot Chicago scenes in the Gramercy Theater and Burger Heaven on 51st Street and found patches of winter road in Westchester as anonymously flat and desolate as any in the Midwest. Many of the West Village locations were shot in the East Village, and even when half a century has left architecture pretty much intact, decor has evolved so drastically that pre-WW2 apartments had to be substantially retrofurbished. Llewyn’s sister’s narrow Queens two-story with the gray asphalt shingles and the Chef Boy-Ar-Dee Cheese Pizza in the cupboard was easier—pure Woodside, even though it’s actually in Ridgewood. The folksingers’ furniture is a jumble of secondhand couches, worn Danish modern, and such perennials as the wine-bottle lamp with the frayed shade in Al Cody’s cramped walkup. And reinforcing “reality” throughout is Bruno Delbonnel’s crucial decision to bathe everything in the cold gray cloud-cover light that dominates every New York winter.

Het effect van al die moeite is dat we samen met Davis door Greenwich Village van toen lopen en The Gashlight bezoeken waar diverse folkzangers een podium vonden. Ook Bob Dylan, waar we aan het eind van de film een glimp van zien.

Greenwich Village was begin jaren zestig het epicentrum van de folk-scene: in de koffiehuizen en clubs in de straten rond Washington Square traden folkzangers en -zangeressen op tijdens open-mike nights in de hoop het publiek aan te spreken en ontdekt te worden. De film speelt echter voor de hype:

The Greenwich Village of Llewyn Davis is not the thriving scene that produced Peter, Paul and Mary and changed the world when Bob Dylan went electric. It is the folk scene in the dark ages before the hits and money arrived, when a small coterie of true believers traded old songs like a secret language. Most were local kids or voyagers from the suburbs of Long Island and New Jersey, fleeing the dullness and conformity of the Eisenhower 1950s to a Bohemian life in lower Manhattan, where a two-person hole-in-the-wall could still be had for twenty-five dollars a month.

Some details of the movie suggest familiar figures—Llewyn’s Welsh name recalls Dylan, and like Phil Ochs he crashes on the couch of a singing couple named Jim and Jean. But the story takes place in the moment before Dylan and Ochs arrived, when no one imagined the Village becoming the center of a folk boom that would produce international superstars and change the course of popular music. This moment of transition—before the arrival of the 60s as we know them—was captured by one of the central figures on that scene, Dave Van Ronk, in his memoir The Mayor of MacDougal Street, which the Coen Brothers mined for local color and for a few key episodes of this week in Llewyn’s life. Llewyn is not Van Ronk, but he sings some of Van Ronk’s songs and shares his background as a working class kid who split his life between playing guitar and shipping out in the Merchant Marine.

Llewyn also shares Van Ronk’s love and respect for authentic folk music, old songs polished by the ebb and flow of oral tradition. For Van Ronk’s generation, the well-worn authenticity of folk provided a profound contrast to the ephemeral confections of the pop music world, and the choice to play folk was almost like joining a religious order—complete with a vow of poverty, since there were virtually no jobs in New York for anyone who sounded like a traditional folk artist. That would change in the early 1960s, and already in early 1961, when Inside Llewyn Davis takes place, there were glimmerings of the world to come—a few small clubs where people could play once in a while for tips, and some little record companies that—though they might not pay much—were at least willing to record the real stuff. Van Ronk recalled that time with a mix of wry humor and deep affection—like Llewyn he was living hand to mouth and sleeping on couches, but he was surrounded by people for whom the music mattered more than anything else. (Bron)

Het verteltempo in Llewyn Davis ligt niet hoog, en dat geeft je alle ruimte om eens goed naar de omgeving te kijken. Dat levert wat mij betreft extra kijkgenot op. Linda en ik zagen de film op eerste kerstdag in The Movies, Amsterdam. De vroege voorstelling van 11.45 werd door ons en een ouder stel bezocht. Verder was de zaal leeg. Dat is pas lekker rustig film kijken.

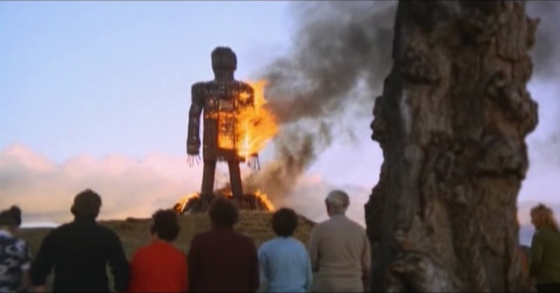

Waarom de rubriek Frames?

De verhalen die we lezen en zien maken net zo goed deel uit van onze levensloop als de gebeurtenissen die we in reallife meemaken. In de rubriek Frames verzamel ik stills uit de films die ik heb gezien om zo die herinneringen te kunnen bewaren en koesteren.