Recently Irish writer Colum McCann visited the Netherlands to promote his new novel TransAtlantic. His Dutch publisher De Harmonie asked me to interview him about the book.

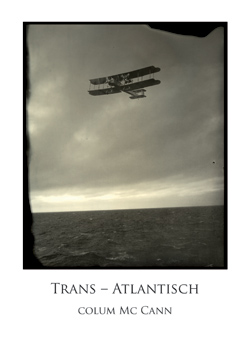

In TransAtlantic McCann connects three iconic crossings. The first non-stop Trans atlantic flight by aviators Jack Alcock and Arthur Brown in 1919; Frederick Douglass, toured Ireland in 1845 and ’46 to promote his subversive autobiography in which he describes his life as a black slave in America. Douglass finds the Irish people sympathetic to the abolitionist cause—despite the fact that, as famine ravages the countryside, the poor suffer from hardships that are astonishing even to an American slave. In New York 1998 senator George Mitchell departs for Belfast, where it has fallen to him to shepherd Northern Ireland’s notoriously bitter and volatile peace talks to an uncertain conclusion. All these narratives are connected by a series of remarkable women whose personal stories are caught up in the swells of history.

In TransAtlantic McCann connects three iconic crossings. The first non-stop Trans atlantic flight by aviators Jack Alcock and Arthur Brown in 1919; Frederick Douglass, toured Ireland in 1845 and ’46 to promote his subversive autobiography in which he describes his life as a black slave in America. Douglass finds the Irish people sympathetic to the abolitionist cause—despite the fact that, as famine ravages the countryside, the poor suffer from hardships that are astonishing even to an American slave. In New York 1998 senator George Mitchell departs for Belfast, where it has fallen to him to shepherd Northern Ireland’s notoriously bitter and volatile peace talks to an uncertain conclusion. All these narratives are connected by a series of remarkable women whose personal stories are caught up in the swells of history.

As in earlier work, McCann combines historic events with fictional elements, and lets real life characters cross paths with fictional characters:

‘One of the recurring themes for the past ten or twelve years of my writing life has been that nebulous line between what’s true and what’s not true. What’s real and what’s not real. What’s imagined and what is supposedly factual. And I like this territory. It’s good territory for a contemporary novelist to be in, because we get fed such a line of bullshit left right and centre by corporations, by governments and by ourselves. One has to doubt what is true and what is not true. There is a very distinct argument to be made that the imagined is as real as the imaginary. The character of Emily Ehrlich in my novel is as real to me as any journalist that would have been around in the early part of the 20th century. And what this does is that it puts the novelist in the position where he or she questions the notion of what’s authentic. And we must learn to question what’s authentic if we are going to live sort of valuable proper lives and not be exploited by artists, by corporations, by governments, by ourselves.’